What’s Love Got to Do with the Balfour Declaration?

How the British prime minister’s affair may have set Middle Eastern turmoil in motion during World War I

By Courtney Suciu

The politics of World War I were a complicated tangle of shifting allegiances and alliances, secret arrangements, double-dealings and vaguely-worded agreements as battles were waged on various fronts throughout Europe and the Middle East.

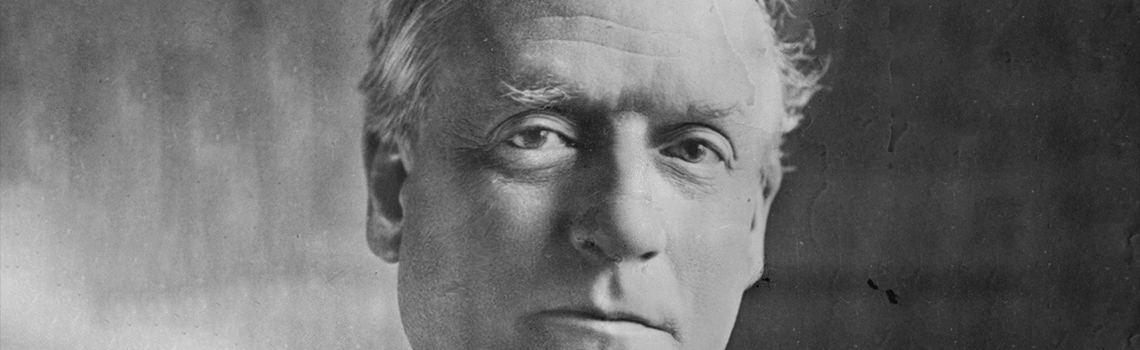

Further complicating this great watershed of 20th century geo-political turmoil: a love triangle involving H.H. Asquith, then-prime minister of Great Britain.

Now, more than a century later, historians continue to ponder how an obsessive love affair – and the publication of an intentionally ambiguous, pro-Zionist document known as the Balfour Declaration – may have resulted in the ongoing conflict between Israel and Palestine.

But first a little background

While the main action of World War I took place in Europe, in the Middle East the Ottoman Empire sided with Germany and declared war against France, Russia and Great Britain. In his article “The Letter and the War,”1 historian David Reynolds compellingly elaborates on the complex situation. But in essence, the Ottoman Empire was a threat to the British Empire, spurring a determination on the part of Great Britain to take a strong position in the region.

In 1916, British and French representatives, Sir Mark Sykes and Francois Georges Picot, negotiated a secret compact. They decided that upon toppling the Ottoman Empire, most of the Arab region would be divided into British and French spheres of influence. After the war ended in victory for the Allied Forces in 1919, Great Britain would oversee the territories eventually known as Syria, Lebanon, Iraq, Palestine and Trans-Jordan.

But that’s getting ahead of things. In 1917, British foreign secretary Arthur Balfour, arguably motivated less by altruism than politics, penned a brief, ambiguously-worded document called the Balfour Declaration. In it, Great Britain promised the international Jewish population a homeland in Palestine.

But even before that, there was yet another complication: a love triangle involving H.H. Asquith, then-Prime Minister of Great Britain. Asquith resigned from office in 1916 shortly after his mistress, socialite Venetia Stanley, cut off their affair in order to marry his friend and cabinet member, Edwin Montagu. Asquith was replaced as prime minister by David Lloyd George, a devout Christian Zionist who championed the Balfour Declaration.

For many scholars, that hastily-written war-time promise is where the seeds for the current Israeli-Palestinian conflict were planted. How might Asquith’s failed romance have helped bring it to fruition?

The prime minister’s passionate obsession

According to the article “The Love Triangle That Changed the Course of Zionism,”2 published in the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, the affair between Asquith and Stanley began in 1910. Then 21 years old and a “liberated woman” for her time, Stanley was close friends with the prime minister’s daughter, Violet (who would later marry and become Violet Bonham-Carter – she was actress Helen Bonham-Carter’s grandmother).

When Asquith, “a known skirt-chaser” who carried on a series of extramarital affairs with “a number of eminent women from the cream of British society,” met his daughter’s companion, he “became totally dependent upon her and obsessed with their relationship,” according to Haaretz.

What actually went on in their relationship is the subject of speculation, but at the very least the pair engaged in an impassioned and prolific letter writing exchange which went on for years. Asquith, who had a reputation as a brilliant and savvy politician, seemed to be putty in Stanley’s hands and often wrote to her many times a day, frequently consulting with his young mistress “on delicate affairs of state, and even security secrets,” Haaretz reported.

However, “there had never been any true reciprocity of emotion between [Stanley] and Asquith,”3 John Grigg wrote in a The Spectator review of H.H. Asquith: Letters to Venetia Stanley, which were published in 1982. (There is no record of Asquith’s letters from Stanley, as the prime minister had them destroyed.) “Naturally she was flattered and fascinated by his extraordinary attentions, and no doubt fond of him, up to a point,” Grigg continued:

but it was impossible for her to return his intense, consuming love, and understandable that she should have wished to escape from a situation which was becoming too difficult to handle. Her way of escaping may have been unnecessarily abrupt and hurtful…

Her way of ending the relationship was to send Asquith a letter on May 12, 1915 informing him of her intention to marry Montagu.

“[Stanley] responded with two short letters, in which his emotional turmoil is plain,” the Haaretz article revealed:

In the first he wrote: "Most loved... As you know well this breaks my heart.... I couldn't bear to come and see you.... I can only pray God to bless you - and help me." In the second letter he wrote: "This is too terrible.... No hell can be so bad. Cannot you send me one word?... It is so unnatural.... Only one word?"

A change in British leadership and politics

But Stanley would have her hands too full to even send one word. In order to marry Montagu, she needed to convert to Judaism, the Haaretz account explained, as his father “stipulated in his will that his son would only inherit his property if he married a Jew” (which was the reason Stanley had turned down his earlier proposal of marriage while carrying on her affair with Asquith).

Stanley’s conversion to Judaism made international headlines. A society pages article from the Peking Gazette4 described the process as “neither simple nor perfunctory,” as the candidate had to “undergo a special course of tuition in Jewish laws and customs” and convince a board of advisor of a “sincerity of belief and knowledge of the Jewish religion.”

And so, according to Haaretz, “two months after she dumped Asquith, on July 26, 1915, Venetia married Montagu in a proper Jewish wedding ceremony.”

Of course, in the midst of all this, the war raged on, and for Great Britain it was not going well. Asquith “soon lost his ability to govern and was forced to resign,” Haaretz claimed, though it’s not clear to what extent his breakup with Stanley fed into his political decline. (The Spectator article pointed out that after his affair with Stanley, Asquith took up writing to her sister, Sylvia, though in a less fevered fashion.)

Either way, Asquith was blamed for a stalemate in the battlefields. Additionally, his disagreement with Secretary of State for War Lloyd George over the creation of a war committee resulted in his resignation from office in December 1916. The reason this is significant in relation to the Balfour Declaration is that the original document was sent on November 2, 1916, when Asquith was still in office.

Had he remained prime minister, its likely nothing would have happened with it. This is because Asquith’s politics regarding the establishment of a Jewish homeland were in large part informed by his close friend and advisor, Montagu – the man who married his mistress.

In his article for the New Statesman, Reynolds explained, “Montagu was an ‘assimilationist’ – one who believed being Jewish was a religion not an ethnicity.” According to cabinet notes quoted by Reynolds, Montagu “urged strong objections to any declaration in which it was stated that Palestine was the ‘national home’ of the Jewish people. He regarded the Jews as a religious community and himself as a Jewish Englishman.”

For Montagu, the historian continued, the “proposed Declaration [was] a blatantly anti-Semitic document and claimed that ‘most English-born Jews’ were opposed to Zionism.”

Paving the way for modern day conflict

When Asquith resigned from office and Lloyd George took over as prime minister, Montagu’s influence diminished significantly. Lloyd George and Balfour were fervent Christian Zionists for reasons both political and religious.

Ambiguously-worded and impossible to fulfill (as the Balfour himself later admitted, according to Reynolds), the Balfour Declaration was officially published on November 9, 1917 during Lloyd George’s ascent to premiership, and when Asquith all but had one foot out the door. The declaration was put into action at a 1920 conference of World War I Allies, and approved by the League of Nations two years later, becoming a cornerstone for the creation of Israel – and the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

For further research on how decades of turmoil in the Middle East can be traced back to the events of World War I, here are some resources to provide deeper insight from a variety of perspectives, from different vantage points in history:

ProQuest History Vault Creation of Israel: The British Foreign Office Correspondence on Palestine and Transjordan, 1940-1948

A collection of primary source documents essential for understanding the modern history of the Middle East, the establishment of Israel as a sovereign state, and the wider web of postwar international world politics.

History Vault also includes the following:

Papers of Harry S. Truman on the U.S. recognition of Israel (this is in the module American Politics in the Early Cold War: Truman and Eisenhower Administrations, 1945-1961

Files on the Arab-Israeli Six-Day War of 1967, from U.S. State Department Records, part of the module, Vietnam War and American Foreign Policy, 1960-1975

Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files on Palestine and Israel, in the module Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files, 1960-1969, Africa and Middle East

Video, books, correspondence, government documents and other primary source materials curated by an international board of scholars, demonstrate the interactions and interconnectedness of global issues. Including:

Scheid, A. L. (Director), & Scheid, A. L. (Producer). (2005). Israel/Palestine: The Shape of the Future [Video file]. Journeyman Pictures. Also available from Academic Video Online.

Caplan, N. (2010). The Israel-Palestine Conflict [Book]. West Sussex, England: Wiley-Blackwell. Also available from Human Rights Studies Online database.

Reubin, R. (n.d.). Israel - Palestine: 'Go Up and Take Possession of the Land'. United Israel Appeal poster, Reuvin Reubin, 1921. In Israel and Palestine Image Collection (p. 4). London, England: Bridgeman Art Library. Also available from Border and Migration Studies Online database.

Long, C. (2017). The Palestinians and British Perfidy: The Tragic Aftermath of the Balfour Declaration of 1917.

Rhett, M. A. (2015). The Global History of the Balfour Declaration: Declared Nation.

Turnberg, L. (2017). Beyond the Balfour Declaration: the 100-year Quest for Israeli–Palestinian Peace.

Historical Newspapers: American Jewish Newspapers

Investigate the rise of Zionism and the formation of U.S. policies toward the state of Israel and events unfolded on the pages of The American Hebrew & Jewish Messenger (1857-1922), The Jewish Advocate (1905-1990), The American Israelite (1854-2000), Jewish Exponent (1887-1990).

Notes:

-

- Reynolds, D. (2017, Nov). The Letter and the War. New Statesman, 146, 26-29,31-33. Available from the Arts Premium Collection, ProQuest Central and Global Newsstream.

- The Love triangle that Changed the Course of Zionism. (2017, Nov 02). Haaretz. Available form ProQuest Central and Global Newsstream.

- Grigg, J. (1982, Nov 27). H. H. Asquith: Letters to Venetia Stanley Selected and Edited by Michael and Eleanor Brock (Book Review). The Spectator, 249, 21. Available from Periodicals Archive Online.

- BRIDE AND CONVERT. (1915, Aug 20). Peking Gazette (1915-1917). Available from Chinese Historical Newspapers.

________________________________________________________________________________

Courtney Suciu is ProQuest’s lead blog writer. Her loves include libraries, literacy and researching extraordinary stories related to the arts and humanities. She has a Master’s Degree in English literature and a background in teaching, journalism and marketing. Follow her @QuirkySuciu