The NAACP’s Anti-Lynching Campaign

We mark the 110th anniversary of the founding of the NAACP, and the recent passage of anti-lynching legislation by the U.S. Senate

By Courtney Suciu

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) was established on February 12, 1909 – a date chosen to coincide with the 100th birthday of the Great Emancipator, Abraham Lincoln. The organization, which came to be best known for its civil rights advocacy, originally formed largely in response to a wave of brutal mob violence against African Americans throughout the South and Midwest.

Made up of an interracial coalition of legal experts and activists, founders of the NAACP included Ida B. Wells and W.E.B. Dubois, two of the fiercest and most vocal anti-lynching crusaders of the era. Only recently, more than a century later, the U.S. Senate passed a bill – after 200 previous attempts – making lynching a federal hate crime.

To mark the 110th anniversary of the founding of the NAACP, we take a closer look at events which galvanized the organization’s anti-lynching campaign, the impact of these efforts and the struggle to enact anti-lynching legislation.

The lynching of Jesse Washington

In May 1916, teenage farmhand Jesse Washington was charged with the rape and murder of his employer’s wife in Waco, Texas. The jury found him guilty of the crime and sentenced him to death. According to a report in the Detroit Free Press1, the moment the verdict was announced, a mob “swept officers aside” and someone cried out “get the negro!”

What happened next is one of the most gruesome incidents of extrajudicial violence in American history. It is widely acknowledged that there were 4,475 lynchings in the US between 1882 and 1968, but Washington’s case was particularly heinous. The Free Press described in detail the torture, burning and hanging of the young man, witnessed in a carnival-like atmosphere by 15,000 spectators, including women and children.

In her book The First Waco Terror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP2, Patricia Bernstein elaborated on what set this incident apart:

Even in the vast bloodbath of lynching that washed across the South and the Midwest during the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Waco lynching stands out. There were so-called race riots in other cities, large and small, in which dozens of black people were injured or killed and whole black neighborhoods destroyed. There were also other supremely hideous lynchings of individuals and small groups of people, but most of these took place in small towns, rural areas, or out in the woods. The Waco Horror – public torture treated as a thrilling spectacle by thousands in a well-established modern city with some pretensions to culture and enlightenment – was unique.

The brazen nature of this incident, the collective acceptance of such sadism as a cause for community celebration, made it more clear than ever that African Americans needed protection and justice. It was an impetus for the NAACP’s anti-lynching campaign and the first order of business was to spread awareness of the problem.

“The Waco Horror” and the NAACP’s anti-lynching campaign

The Crisis magazine, the official publication of the NAACP, published its first issue in 1910 under the editorial helm of W.E.B. Dubois (and it remains the oldest, continuously-run Black publication in the world). In his dissertation, W.E.B. Dubois as Editor of “The Crisis,”3 Martin Gordon Kimbrough wrote that the July 1919 issue “carried a lynching supplement, ‘The Waco Horror,’ an eight-page pamphlet concerning the case of Jesse Washington,” as investigated by white suffragist Elizabeth Freeman.

Hired by the NAACP to investigate the lynching of Washington, Freeman spent a week in Waco posing as a reporter interviewing Black and white members of the community, including the eyewitness of the incident, family of both the murdered woman and Washington, and local authority figures. Bernstein described this effort as “an extraordinary act of courage” as “NAACP representatives who tried to investigate racial incidents in the South in similar circumstances were threatened with bodily harm or actually attacked.”

The grisly details Freeman uncovered, along with graphic images of Washington’s charred body, were published by Dubois in “The Waco Horror” supplement which was “distributed to 42,000 Crisis subscribers, 700 white newspapers, and fifty Negro Weeklies, and to others who were willing to aid the N.A.A.C.P.'s Lynching Fund Campaign,” according to Kimbrough.

Through this effort to promote awareness of the Waco lynching, the NAACP provoked widespread support for its anti-lynching campaign. Dubois wrote in “The Waco Horror,” The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People proposes immediately to raise a fund of at least $10,000 to start a crusade against this modern barbarism.”

Details gleaned from The Crisis supplement on the lynching of Washington, along with a call for donations to the NAACP appeared in an article by the organization’s secretary, Roy Nash, who made this plea in the Chicago Defender4:

Those who believe that a cry to heaven should be raised against this and every lynching, by legal prosecution, by publicity, by co-operation with the best white element in the south, by political agitation, are urged to assist the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People to raise this $10,000.

The NAACP’s campaign to raise awareness of lynching also included publicity of ongoing incidents of lynching, as well as sponsored conferences, lectures and rallies to promote anti-lynching legislation.

The Dyer Act and other attempts at anti-lynching legislation

The first anti-lynching bill came from Republican Congressman Leonidas Dyer of Missouri in 1918. Originally the NAACP declined to support the Dyer Bill as the organization’s first president, lawyer Moorfield Storey found it unconstitutional but changed his position in 1919.

A news release5 issued by the NAACP in June 1922 cited a letter from Congressman Dyer expressing the urgency of this legislation:

I feel that the situation is so serious that no delay other than absolutely necessary should be permitted. The most horrible lynchings are now taking place in some of the states of the union. The Congress certainly ought to legislate if it has the authority to do so. It is beyond dispute that the States are unable to protect citizens of the United States resident in the respective states where lynchings are going on.

He went on to argue that if his bill was deemed unconstitutional for usurping States’ rights, then an amendment to the Constitution should be introduced.

The House of Representatives passed the Dyer Bill in January 1922 but, according to The Washington Post, “Southern Democrats in the Senate filibustered, and Republicans, who held the majority, allowed the bill to die."

A movement to enact similar legislation was mounted in 1934 with the Costigan-Wagner Bill, which The Post noted was lobbied by First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt but not promoted by President Franklin Roosevelt who needed the support of Southern Democrats for his New Deal agenda. It was also defeated by filibuster in the Senate. Another anti-lynching bill sponsored by New York Representative Joseph Gavagan met the same fate in 1937.

In the following decades, 200 attempts to pass anti-lynching legislation would be introduced to Congress and fail to make it into law.

But on December 19, 2018 the Justice for Lynching Act, proposed by Senators Kamala Harris, Cory Booker and Tim Scott, passed the Senate unanimously. The bill states, “The crime of lynching succeeded slavery as the ultimate expression of racism in the United States following Reconstruction,” and that “Only by coming to terms with history can the United States effectively champion human rights abroad."

According to this legislation, if two or more people acting together are convicted of killing someone because of their "actual or perceived race, color, religion, or national origin," they can be sentenced to up to life in prison. Perpetrators of lynching who inflict “bodily harm” will face a minimum of 10 years in prison.

To date, the 2018 Justice of Lynching Act has yet to pass the U.S. House of Representatives and be signed into law by President Trump.

For more information, click on the product links below.

ProQuest History Vault NAACP Papers

The NAACP Papers in ProQuest History Vault include an entire section focused on lynching and discrimination in the criminal justice system. Press releases, investigative reports, pamphlets, speeches, and letters to editors and public officials show how adroitly its staff and officers stressed these realities to redirect public attitudes against mob rule. These documents disclose the human equations in the fight against mob terrorism, from the grief and appeals for help by beleaguered survivors of a lynched victim; to the details of impending lynchings, some of which were actually advertised by newspaper and radio in advance; and the personal sacrifices of such NAACP officers as Walter White, Daisy Lampkin, William Hastie, Thurgood Marshall, and John Shillady in confronting racist violence.

Brown, T. (Producer). The Longest Struggle, Part 1: Reign of Terror, in Tony Brown's Journal. [Video/DVD] Tony Brown Productions.

Ida B. Wells: A Passion for Justice. Greaves, W. (Director). (1989, Oct 24).[Video/DVD] California Newsreel.

NAACP. (2009, Jan 01). 60 Minutes.[Video/DVD] New York: BBC Studios Americas, Inc., Columbia Broadcasting System.

Strange Fruit. Katz, J. (Director). (2002, Jan 01) [Video/DVD] California Newsreel.

ProQuest Black Historical Newspapers

Discover source material essential to the study of American history and African-American culture, history, politics, and the arts. Examine major movements from the Harlem Renaissance to Civil Rights, and explore everyday life as written in the Chicago Defender, The Baltimore Afro-American, New York Amsterdam News, Pittsburgh Courier, Los Angeles Sentinel, Atlanta Daily World, The Norfolk Journal and Guide, The Philadelphia Tribune, and Cleveland Call and Post.

Notes:

-

- BURN NEGRO AT STAKE IN WACO; 15,000 WATCH. (1916, May 16). Detroit Free Press (1858-1922). Available from ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Bernstein, P. (2006). First Waco Horror: The Lynching of Jesse Washington and the Rise of the NAACP. Available from Ebook Central.

- Kimbrough, M. G. (1974). W. E. B. Dubois As Editor Of "The Crisis". (Order No. 7504405). Available from ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global.

- Nash, R. (1916, Jul 29). WACO HORROR STIRS RACE TO ACTION. The Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Edition) (1905-1966). Available from Black Historical Newspapers.

- Papers of the NAACP, Part 07: The Anti-Lynching Campaign, 1912-1955, Series B: Anti-Lynching Legislative and Publicity Files, 1916-1955. Folder: 001529-013-0764. Available from ProQuest History Vault Civil Rights and the Black Freedom Struggle collection.

- Masur, L.P. (2018, Dec 28). Why it took a century to pass an anti-lynching law. Available from Global Newsstream and ProQuest Central.

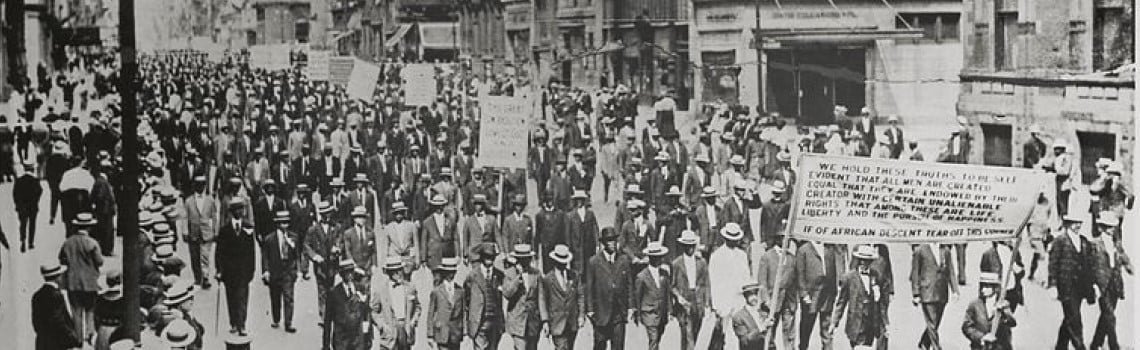

*Public domain image from the Silent Parade, July 28,1917 in New York City, co-organized by the NAACP to protest anti-Black violence and promote anti-lynching legislation.

Courtney Suciu is ProQuest’s lead blog writer. Her loves include libraries, literacy and researching extraordinary stories related to the arts and humanities. She has a Master’s Degree in English literature and a background in teaching, journalism and marketing. Follow her @QuirkySuciu