La Causa and the Power of Solidarity

A tribute to the millions of people who unified in support of migrant farm workers in the 1960s

By Courtney Suciu

Since the early 20th century, large-scale agriculture in the U.S. has depended on migrant workers, a largely unorganized, underpaid and powerless workforce. But in 1965, 800 Filipino farm workers with the Agricultural Workers Organizing Committee launched a strike in Delano, California to demand higher pay. Soon after, 2000 Mexican farm workers with the National Farm Workers Association eagerly joined the cause.

The two organizations merged, forming the United Farm Workers (UFW) under the aegis of the AFL-CIO (the largest federation of unions in the U.S.) and generated widespread attention to their struggle. Various organizations – from steel workers’ unions to teachers’ unions, as well as churches and civil rights groups – joined picket lines and refused to purchase grapes until the UFW signed its first union contracts.

In 1970, the strike and boycott against the grape growers ended in victory. Previously, big agricultural enterprises had been able to take down labor activists through violence or negotiating one-time pay increases. This time, the UFW achieved the right to organize and bargain collectively, and secured better wages for its members.

Whether considering the scope of labor history or scanning the recent headlines, it’s clear that executing a successful boycott is not an easy feat. So how did La Causa, as this farm workers’ movement came to be known, garner the support of millions of everyday Americans necessary to bring about such an accomplishment?

The struggle of farm workers became a national movement

In November 1969, The New York Times reported on a protest featuring several hundred demonstrators marching though Pittsburgh’s wholesale produce market. Steven V. Roberts wrote:

It was a motley group. There were housewives in well-tailored slacks and students in faded jeans, priests in Roman collars and blacks with Afro hair-do’s, a few businessmen in conservative suits and a barrel-chested union leader. But they all had the same message – don’t eat the grapes.

At a divisive time, when the nation was polarized by racial tensions and the Vietnam War, the grape boycott made many Americans feel empowered to elicit change. For various reasons, this was a cause that resonated with people from different backgrounds and across social divides:

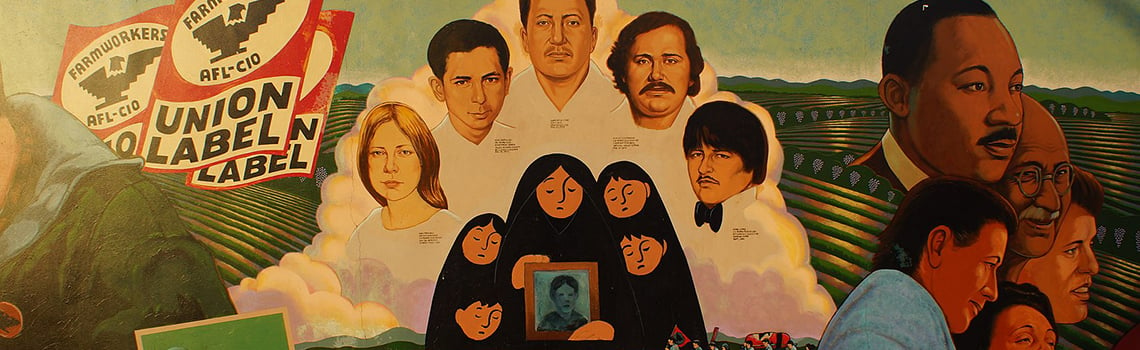

The soft-spoken, charismatic leader of the UFW Cesar Chavez brought a spiritual component to the movement in the tradition of Mahatma Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. with his fierce commitment to civil disobedience.

UFW co-founder Dolores Huerta took the plight of the farm workers to consumers so that they understood the power they wielded spending – or not spending – their dollars, and she injected a healthy dose of feminism into the cause.

Civil rights and Black freedom activists related to a marginalized population abused and exploited by a white capitalist system.

Members of labor unions, especially those within the AFL-CIO, heeded the call of solidarity as the backbone of workers’ rights.

Let’s take a closer look at a few of these dynamics and how they factored into the success of the 1960s grape boycott.

Race and La Causa

In his New York Times’ piece, Roberts noted how the UFW “welcomes the help of everyone,” making the boycott “particularly attractive at a time when white liberals often feel rejected by Black leaders and uneasy at the increasing talk of violence.”

Even as La Causa was welcoming to white liberals, it also attracted more radical activists and Black freedom organizations “though they sometimes differ on tactics,” Roberts reported. “In New York, an alliance with the Black Panthers was quietly dropped when several stores selling grapes were mysteriously firebombed.”

The farmer workers’ movement also appealed to Black leaders of the civil rights movement who were committed to nonviolence, including Rev. Ralph Abernathy, leader of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which he co-founded with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. According to a 1969 report from the Atlanta Constitution2, Abernathy appeared with a “Viva la Huelga” (“long live the strike”) button pinned to his suit when he spoke at rally with Mexican American farm workers.

“We are going to sock it to the United States with black and brown and yellow power,” he told the crowd, elaborating on the how the experience of U.S. slaves related to their struggle. “I am a Mexican American too. I grew up on a farm only we did not pick grapes, we picked cotton…My mother and father were not adequately paid for their labor, but I’ll be dogged if we’re not going to see you’re adequately paid for your labor.”

Support from church groups

As Black ministers like Abernathy appealed to their congregations to support La Causa, other church leaders did the same. In 1968, an “Interfaith Action Coalition” was formed in Southern California to support the grape boycott.

In the Los Angeles Times3, Harry Bernstein interviewed the president of the Presbyterian Interracial Council who said that the alliance of “Catholic, Protestant and Jewish faiths will distribute leaflets in support of the boycott at churches and synagogues, deliver sermons on the issue, include it in special Labor Day sermons and set up churchmen’s picket lines where it is possible.”

In a 1970 issue of U.S. Catholic4 magazine, Father Mark Day wrote an editorial the on moral imperative of Catholics – and all Americans – to support the movement. “The real problem” facing Americans, he argued, “is that there is not more widespread moral outrage.”

Day detailed the reasons why the living and working conditions of the farm workers should be cause for such outrage: “Farm workers are excluded from unemployment coverage. They still do not possess the right to bargain collectively with their employers under federal law. Health and sanitation laws are ignored by 90% of agricultural employers,” he noted.

“The question is not: should I buy grapes or not?” Day concluded. “The question is: What can I do to help the boycott as long as growers refuse to come to the bargaining table? Am I needed in a picket? Can I organize a committee to distribute leaflets or schedule a rally?”

Widespread union partnerships

Day’s call for action was right in alignment with the support unions within the AFL-CIO encouraged. Affiliates such as the American Federation of Teachers urged members to “join actively in the national boycott against struck California grape growers,” according to the American Teacher union publication.5

The AFL-CIO sought “full labor support for the ‘newest and neediest’ member of the family of organized workers” according to the article, which included an image of striking farm workers who came to the AFT convention in Cleveland to bolster cooperation from the teachers.

Rallying unions for support didn’t end when the strikers from Delano at last signed a contract with fruit growers. UFW leader Chavez spoke directly to delegates at the 8th Convention of California Labor Federation AFL-CIO6 in September 1970 about the ongoing struggle of farm workers throughout the state, including lettuce pickers in Salinas.

He appeared along with Larry Itliong, assistant director of the United Farm Workers Organizing Committee, who implored the crowd to continue working together. “We have many, many farm workers to organize,” he said.

“And this is a challenge not only to the leadership of the labor movement here in California especially, if not the entire nation. We have a problem, all of us together,” he continued, evoking the spirit of solidarity necessary to combat oppression: “You have just as much responsibility to get the farm workers organized.”

Considering the long-term impact of La Causa

Unfortunately, the farm workers movement was not able to maintain the momentum it created in the early 1970s. By the mid ‘70s, organized labor in the U.S. was on the defensive and losing political power. But this chapter in history remains critical for understanding ongoing issues related to workers’ rights and organized labor.

What has been the long-term impact of the farm workers movement of the 1970s? How have working conditions for farm workers changed between the 1970s and the first two decades of the 21st century? Why did American labor unions become less influential, in the workplace and in politics, during the 1970s?

These are just a few of the many questions researchers might ask about workers and organized labor in the last 100 years. Explore ebooks, journals, dissertations, and primary sources that can help researchers consider questions like these and a wide variety of other topics related to the history of American labor and working conditions in the U.S. and around the world.

See a wide array of resources, including related essays and watch the video sample The Golden Cage: A Story of California's Farmworkers, available in Academic Video Online.

For further research

Araiza, L. (2013). To March for Others: The Black Freedom Struggle and the United Farm Workers.

Brill, M. T. (2018). Dolores Huerta Stands Strong: The Woman Who Demanded Justice.

Bruns, R. A. (2011). Cesar Chavez and the United Farm Workers Movement.

Kallen, S. A. (2010). We Are Not Beasts of Burden: Cesar Chavez and the Delano Grape Strike, California, 1965-1970.

Ganz, M. (2009). Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement.

Watt, A. J. (2010). Farm Workers and the Churches: The Movement in California and Texas.

Educational Video Group (Producer). (n.d.). Cesar Chavez: "The Power of Non Violence" [Video file].

The Latino List, Vol. 2: Sexism: Dolores Huerta's Story [Video file]. (n.d.).

Ferriss, S. (Producer). (1991). The Golden Cage: A Story of California's Farmworkers [Video file]. Filmakers Library.

The Labor Unions in the U.S., 1862-1974: Knights of Labor, AFL, CIO, and AFL-CIO module includes digitized primary source documents revealing the growth, transformation, successes and failures of one of the important American social movements of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the modern American labor movement, made available in partnership with Catholic University of America.

The Workers, Labor Unions, and the American Left in the 20th Century: Federal Records module has a special emphasis on the interaction between American workers, labor unions, and the federal government. Learn more.

Notes:

- By STEVEN V ROBERTS Special to The New York Times. "Grape Boycott: Struggle Poses a Moral Issue." New York Times (1923-Current file), Nov 12, 1969, pp. 49. Available from ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Abernathy Rallies for Grape Boycott. (1969, May 18). The Atlanta Constitution (1946-1984). Available from ProQuest Black Historical Newspapers.

- Bernstein, Harry. "Church Leaders Unite to Back Grape Boycott." Los Angeles Times (1923-1995), Aug 14, 1968, pp. 2-b1. Available from ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Day, M. (1970, 03). “The grape boycott should be supported.” U.S.Catholic, 35, 14-17. Available from Religious Magazine Archive.

- Grape boycott grows. (1968). American Teacher, 53(1), 14. Available from Education Magazine Archive.

- ProQuest History Vault: State Labor Proceedings: AFL, CIO and AFL-CIO Conventions, 1885-1974 collection; Labor Unions in the U.S., 1862-1974: Knights of Labor, AFL, CIO and AFL-CIO module. Folder: 000986-000-0021

________________________________________________________________________________

Courtney Suciu is ProQuest’s lead blog writer. Her loves include libraries, literacy and researching extraordinary stories related to the arts and humanities. She has a Master’s Degree in English literature and a background in teaching, journalism and marketing. Follow her @QuirkySuciu