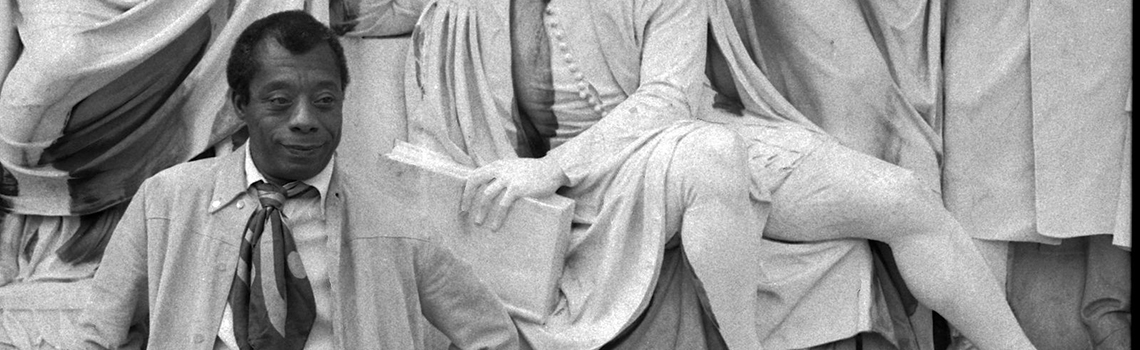

James Baldwin’s Threat to the Status Quo

“…Look the world in the face like you have a right to be here. When you do that, you have attacked the power structure of the western world.”

In 1999, James Baldwin scholar James Campbell won a decade-long court battle to access FBI files kept on the internationally renowned novelist and social critic. Under the Freedom of Information Act, Campbell sought records that revealed how the Bureau monitored Baldwin’s civil rights activity.

It’s well known that the FBI kept robust records on civil rights and Black power activists, as far back as 1918. Black labor union leaders and socialists, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the organization he founded, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and the Black Panthers are just some of the most high-profile targets of the FBI, singled out to be discredited and surveilled.

Baldwin’s file contained 1,884 pages – an unprecedented number of documents compiled by the FBI on any writer.

One can’t help but wonder, what made Baldwin such a person of interest for the intelligence agency?

“They have always known you are not a mule”

Baldwin was a novelist, short story writer, playwright and prolific social critic. His politics tended toward anti-imperialism. He was also Black and gay. All of this would have been enough to garner the attention of the FBI. But above all, Baldwin was human, and no matter in which forum or genre he communicated, Baldwin’s humanity always shimmered like a beacon to others who have felt lost or struggled to claim their place in the world. This is what made him so beloved to readers and such a unique figure in the civil rights movement.

But his humanity, as he saw it, also threatened the status quo. By compelling us to acknowledge the humanity of people who have been systematically dehumanized in our culture, he showed us the cracks in our foundation. This made him dangerous.

In a 1968 lecture delivered to a diverse group of students in London1, Baldwin recalled being asked where he was from. The answer – New York – didn’t satisfy the inquirer. But, Baldwin explained, it wasn’t possible for him to know where his family originated. “I’m American,” he said, meaning his only heritage was as a Black man living in this country, descended from slaves.

He elaborated on how he got here:

I was handcuffed to another man from another tribe with language I did not speak. We did not know each other and we could not speak to each other because if we could have spoken to each other, we might have figured out what was happening to us and we might have been able to prevent it. It would have created a kind of solidarity which is a kind of identity which might have made the history of slavery very different.

Deprived of his native heritage, and this alternative history, Baldwin, like those who came to America in this way, had to claim own his identity and humanity, which meant “you try to stand up and look the world into the face like you have a right to be here…When you do that, you have attacked the power structure of the western world,” he said.

He went on to debunk some of the myths of slavery and acknowledged the violence of the system upon which this structure was literally built by Black labor, not “out of love,” he said, “but under the whip”:

If I, one fine day, discover that I have been lied to all the years in my life and my mother and my father were being lied too, if I discover that, in fact, though I was bred and bought and sold like a mule, but I know I never really was a mule. If I discover that I was never really happy picking all that cotton and digging in all those mines to make other people rich. And if I discover that those souls sang songs that were not just the innocent expressions of primitive people but extremely subtle and difficult, dangerous and tragic expressions of what it felt like to be in chains, [it will] begin to frighten the white world.

“They have always known that you were not a mule,” he added. “They have always known that no one wishes to be a slave.”

The Literacy Criticism of the FBI

Baldwin wasn’t the only Black writer surveilled by the FBI. He was in the company of such bards of the civil rights movement as Langston Hughes and Amiri Baraka, among many others. In 2006, scholar William J. Maxwell “set out to learn just how many authors guilty of being Black and sometimes blue had attracted files at Hoover’s FBI,” and found “fifty-one declassified but mostly unpublished FBI files on individual authors, ranging from 3 to 1,884 pages each, that together capture the Bureau’s internal deliberations on half a century of African American literary talent.”

Maxwell’s 2015 book F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover’s Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature2 delves deeply into these findings to expose the FBI’s hostility and paranoia directed at five decades of poems, plays, essays and novels by Black writers. In his introduction, Maxwell explained that his intention was to:

[mine] Bureau files for traces of the uneasy intimacy of African American writing and FBI ghostreading, the latter an almost exclusively white occupation under Hoover’s leadership. In the process, I dissect evidence of the criminal intent of Hoover and Sullivan’s [former head of the FBI’s intelligence operations] “Black hate” counterintelligence program and other authentically scandalous chapters of Bureau surveillance. But my overarching aim is to read the files responsively as well as judgmentally, and to reconstruct rather than prosecute the meddling of the FBI in Afro-modernist letters.

In a chapter called “The FBI Is Perhaps the Most Dedicated and Influential Forgotten Critic of African American Literature,” Maxwell zeroes in on the time FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover “returned an FBI memo on the problem of James Baldwin with a handwritten challenge: ‘Isn’t Baldwin a well-known pervert?’” What followed was an unlikely close-reading and critique of Baldwin’s barrier-breaking novels which contain themes of interracial and homosexual relationships.

According to Maxwell, FBI officer M.A. Jones responded by:

distinguishing between fictional and personal testimonies. ‘It is not a matter of official record that he is a pervert,” Jones stipulated, even though “the theme of homosexuality has figured prominently in two of his three published novels…While it is not possible to state that he is pervert,’ Jones concluded, Baldwin ‘has expressed a sympathetic viewpoint about homosexuality on several occasions, and a very definite hostility toward the revulsion of the American public regarding it.’’

Hoover and other members of the Bureau continued with other attempts to try and ban Baldwin’s work, including under the Interstate Transportation of Obscene Matter statute, particularly in regard to his novel Another Country, which depicted a controversial love scene between a mixed-race couple.

Throughout his career, Baldwin expressed frustration at being labeled a Black writer or a gay artist. He was able to transcend such categorization by writing from the perspectives of a variety of humans, populating his novels with male and female, Black and white, gay, straight and bisexual characters. In doing so, his writing was frank and daring in a way that set him apart from other writers of the civil rights era and made him appealing to a wide range of readers.

Between his outspokenness and massive influence, it’s not surprising that Baldwin’s ideas were deemed dangerous and subversive by those whose charge it was to maintain “the power structure of the Western world.” As additional FBI documents and other government records from the civil rights era continue to be released, we have opportunities to gain new insight and deeper understanding into the ongoing struggle between the advocates of social justice and the agents of the status quo.

Sources cited:

-

- Educational Video Group (Producer). James Baldwin: Speech on Civil Rights [Video file]. Available from ProQuest One Academic.

- Maxwell, W. J. (2015). F.B. Eyes: How J. Edgar Hoover's Ghostreaders Framed African American Literature. Available through Ebook Central.

Learn more on the James Baldwin author page in the ProQuest One Literature database.