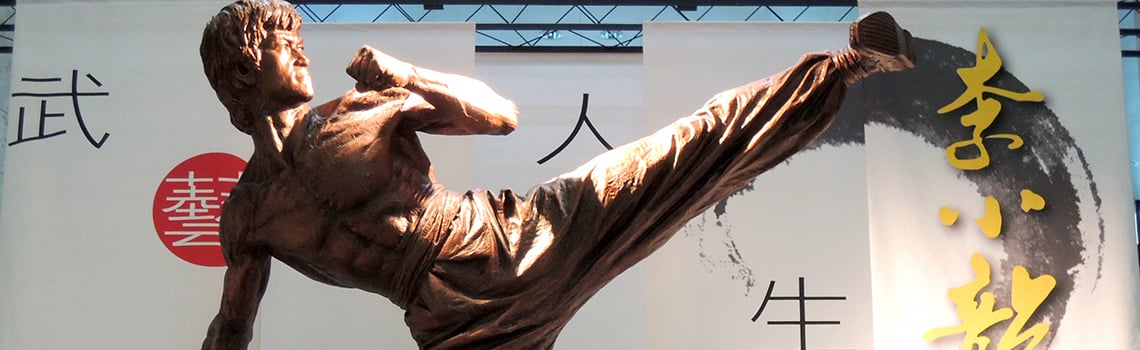

How Bruce Lee Revolutionized American Culture

On the 45th anniversary of Enter the Dragon, we celebrate the ways Bruce Lee’s legacy lives on

By Courtney Suciu

Considered the greatest martial arts film of all time – as well as one of the most influential films, period – Enter the Dragon is not only an extraordinary work of entertainment, it is also a crucial look at changes in early ‘70s American culture. Combining elements of another ethnic movie subgenre, Blaxploitation (where black characters were portrayed as heroes central to storylines rather than as victims and sidekicks), with evolved depictions of post-colonial Asian people and culture, Enter the Dragon was unlike any other film to light up the silver screen.

Bruce Lee was the first actor to bridge East and West. He was from Hong Kong and the U.S. He understood how to speak to both audiences in a way that no one else ever had. Enter the Dragon was the first film co-produced in Hong Kong and Hollywood. This meant Asian landscapes and characters weren’t constructed by American filmmakers. More importantly, Chinese filmmakers had some control over how they appeared on screen. (Compare that to some of the decade’s more problematic depictions of Asian people, particularly films about the Vietnam War.)

There are so, so, so many avenues for researchers to explore Bruce Lee’s overwhelming influence on the action movie genre and on the ways marginalized people are represented in film, and how his influence contributed to a shift in the overall culture of the West. For this blog post, with great difficulty, we’ve had to limit ourselves but at the end of the article we’ve included a sample of the vast resources for further research or just for some fascinating reading.

Changing perceptions of Asians in the American psyche

In a 1981 article for the Journal of Popular Film and Television, scholar Hsiung-Ping Chiao1 made a compelling observation: In the 1977 movie, Saturday Night Fever, there is a scene where Tony (played by John Travolta) is standing in his bedroom. On the walls, we can see two posters. One is of Sylvester Stallone in Rocky; the other is of Bruce Lee.

“Both men,” Chiao noted, “show their bare chests, displaying masculine virility. These icons are too obvious to be arbitrary,” he continued:

The three separate screen images, Travolta, Stallone, and Lee, interlock and are meant to conjure up similar qualities. The fact that these screen characters all come from the lower classes and attain reputations as cult figures in purely physical terms – disco, boxing, and kung fu – reflected the obsession of the 1970s with physical grace and strength. Ethnic charms also are emphasized…but Stallone and Travolta are of white European background. The case for Bruce Lee is more unconventional.

Chiao went to on juxtapose the previous century of derogatory images of Chinese people on screen, “complementing the political ideology of the ‘Yellow Peril’" with stereotypes of “the insidious, vicious Fu Manchu, the obese, inscrutable Charlie Chan and the mob of unidentifiable farmers and railroad workers.”

After the debut of Lee’s second major film role in Fists of Fury, “the Chinese screen image was altered sharply.”

A new way for audiences to relate to action film

Part of Lee’s ability to break out across racial and cultural divides had to do with the universal nature of the themes in his movies. “Lee’s films are virtually products of people’s insecurity and paranoia,” Chiao pointed out. “The majority of the audience longs for a means to clean up the world of rampant crime and injustice.”

With kung fu, anyone willing to do the training could be the hero. Unlike previous action stars who needed guns and other weapons, Lee showed that all a person needs to fight is their own body – an empowering message that appealed to working class audiences of every ethnic background. In Lee’s universe, Black, white and Asian martial artists worked together against the bad guys – and they didn’t need fancy James Bond gear or even the Duke’s six-guns to do it.

Another reason the action in Lee’s films related to audiences had to do with his insistence that “the fewer camera tricks the better,” Chiao wrote. “Long shots were used often and cuts were reduced,” he continued, “so audiences could tell they were watching genuine kung fu instead of camera depictions. Lee’s choreography thus transmitted a sense of fidelity that impressed Western audiences as well as Eastern ones.” Audiences could better relate to the action in Lee’s films because what they witnessed was real people performing the action – not a bunch of gimmicks that evaded reality. This realism inspired a sense of “hey, I could do this too!” among film audiences. But, ironically, such flawless fight sequences couldn’t be achieved by just anyone. “[T]ranscendence and elasticity rely on basic old form,” Chiao pointed out, which was why Lee also insisted on having actual skilled martial artists appear in his films rather than actors, a trend which would endure in the kung fu genre, and inspired an enduring American reverence for the art of martial arts.

For further research

A sample of titles from Ebook Central

Bowman, Paul (2013). Beyond Bruce Lee: Chasing the Dragon through Film, Philosophy, and Popular Culture.

Lee, B. (2015). Bruce Lee: The Art of Expressing the Human Body.

Lee, B. (2015). Bruce Lee Striking Thoughts: Bruce Lee's Wisdom for Daily Living.

Lee, B. (2009). Bruce Lee: Wisdom for the Way.

Little, J. (Ed.). (2007). Words of the Dragon: Interviews, 1958-1973.

There’s a dissertation for that! Selections from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global

Cha, J. (2010). Cross-ethnic Traffic: Performing Ethnicity in Asian/America (Order No. 3441489).

Chen, X. (2016) Kung Fu Moves American Movies (Order No. 10107555).

Chong, S. S. H. (2004). The Oriental Obscene: Violence and the Asian Male body in American Moving Images in the Vietnam Era, 1968–1985 (Order No. 3146815).

Karki, D. B. (2011). The Action Hero in Popular Hollywood and Hong Kong Movies (Order No. 3450423)

Yip, M. F. (2011). Martial Arts Cinema and Hong Kong Modernity: Bodies, Genders, and Transnational Imaginaries. (Order No. 3472980).

ProQuest Screen Studies Collection

A comprehensive survey of current publications related to film scholarship alongside detailed and expansive filmographies, with lots of content related to Bruce Lee and Enter the Dragon. This collection includes the American Film Institute (AFI) Catalog, Film Index International (FII), and FIAF International Index to Film Periodicals Database

Notes:

-

- Chiao, Hsiung-Ping. "Bruce Lee: His Influence on the Evolution of the Kung Fu Genre." Journal of Popular Film and Television, vol. 9, no. 1, 1981, pp. 30.

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Courtney Suciu is ProQuest’s lead blog writer. Her loves include libraries, literacy and researching extraordinary stories related to the arts and humanities. She has a Master’s Degree in English literature and a background in teaching, journalism and marketing. Follow her @QuirkySuciu