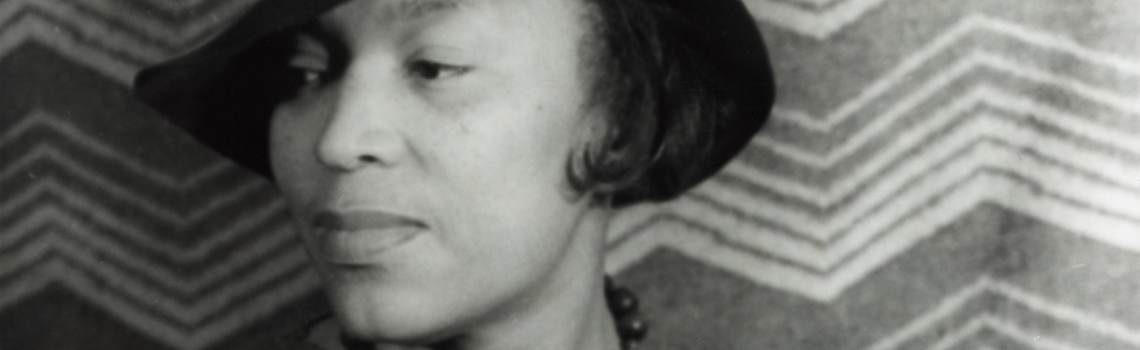

When Hurston Had a (Mule) Bone to Pick with Hughes

Did Zora Neale Hurston’s refusal to compromise with Langston Hughes secure her literary legacy?

Earlier this year, the publication of Zora Neale Hurston’s first full-length book, Barracoon, caused a major ripple in the international literary world. For several decades the work sat unknown except to the most fervent scholars until the Hurston estate decided to have the story at long last available to the public.

This development reminded us of another work by Hurston, Mule Bone, written in 1930 and unpublished until 1984 – nearly 20 years after her death. Hurston penned Mule Bone, a dramatic folk-comedy, in collaboration with her fellow pillar of the Harlem Renaissance, Langston Hughes. The concept of Mule Bone was based on a folktale she’d learned in Eatonville, the all-Black Florida community where Hurston grew up and conducted much of her anthropological research.

When she presented the idea for the play to Hughes, Hurston wasn’t just seeking his help in writing a play. She had a vision for a new kind of theater intended for African American audiences, penned by African American authors, depicting life the way they lived it, in opposition to the Black stereotypes of minstrel shows created to entertain mainstream, mostly white audiences.

Why did it take so long for Mule Bone, an important, insightful piece of Hurston’s literary legacy, to get published? And why, when it finally made its stage debut on Broadway in 1991, was it such a flop?

A “fragmented and problematic” collaboration

Clues for what went wrong with Mule Bone are laid out in a review of the 1991 performance by New York Times critic Frank Rich1:

On occasion – rare occasion – this rendition does make clear what Hurston and Hughes had in mind, which was to bring to the stage, unfiltered by white sensibilities, the genuine language, culture and lives of black people who had been shaped by both a rich African heritage and the oppression of American racism.

Despite these moments of clarity in the production, Rich claimed that the play’s text “often feels like a rough draft in which two competing voices were trying to make a compromise,” and he wondered “Perhaps if the writers had had the chance to finish Mule Bone and to see it with an audience, they would have tightened or rethought what was a work in progress.”

For the most part, the play was plagued by the “fragmented and problematic” “aborted collaboration” of Hurston and Hughes. Whatever caused the legendary rift between the writers is the stuff of much speculation, but Rich noted that most accounts agree that it “at the very least involved a battle over authorial credit.”

In her dissertation, The Fire that Genius Brings: Creativity and the Unhealed Companionship Between Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes, scholar Sharon Dorothy Johnson2 took a unique tack in examining the failed relationship. She wrote:

These two people [Hurston and Hughes], who hung out together, corresponded almost daily, supported each other emotionally, and at times financially, shared immense talent and similar desire and goal to represent Black life in all of its color and complexity. This intimate bond was unraveled by a dispute over authorship of Mule Bone, to the point that, according to Hughes, they never spoke to each other again after that.

Johnson employed tools of Jungian theory to criticize most conventional scholarship on the relationship between two of the most iconic writers of the Harlem Renaissance. She makes the case that much of this scholarship is rooted in “patriarchy and sexism” so that “Hurston bears the burden of being seen as the villain, responsible for the demise of her friendship and creative collaboration with Hughes.”

One of the critics Johnson takes to task is Henry Louis Gates, who according to Johnson noted that Hurston’s act of copywriting Mule Bone in her name only sparked the disintegration of their friendship. However, Johnson made the case that “Hurston should have registered a draft solely in her name, albeit before soliciting Hughes, or anyone else, for feedback or input,” as “the text of the play is based on ‘The Bone of Contention,’ Hurston’s previously unpublished short story inspired by a folktale she collected during her academic research and fieldwork in the Deep South.”

The original story (like much of Hurston’s writing) was steeped in the “rituals, traditions and vernacular that Hurston knew well as a child growing up in Eatonville,” Johnson wrote, and she rejected changes that Hughes made which turned the story’s central plot point, an argument about turkey, into an argument about a woman. The play, meant to be about a religious and political dispute, Johnson continues, became the story of a love triangle, undermining the original folktale on which it was based.

From this point of view, could it be argued that Hurston took action that, though unfair, was necessary to protect her intention of authentically depicting the lives of people in Eatonville – a critical component of her literary legacy?

Why Mule Bone remains a critical piece of Hurston’s legacy

Johnson also takes issue that much of Hurston’s writings, including Mule Bone, “were sanctioned and edited by Gates [so] that his editorial decisions, voice, and scholarly interpretations dominate the landscape” of her work. While Johnson raises a critical point, it’s also important to note Gates was a staunch champion of bringing Hurston’s work to the public. Many works, including Mule Bone, wouldn’t likely be accessible to us if it had not been for Gates’ commitment to publishing Hurston’s entire body of literature in the 1980s.

When the Mule Bone was finally published in 1984 (thanks to Gates), it stirred up a whole new generation of controversy, “particularly among Black readers and critics who were uncomfortable with “the exclusive use of Black vernacular as the language of drama,” he wrote in The New York Times.3

Gates explained that Mule Bone “portrays what Black people say and think and feel – when no white people are around,” adding that “the experience [of the play] called to mind sitting in a barbershop or a church meeting – any number of ritualized or communal settings.

“The boldness of Hughes and Hurston,” he continued, “was that they dared to unveil one of these ritual settings and hoped to base a new idea of theater on it.”

The merits of staging the play were debated at a forum in 1988, where Gates recalled one contemporary playwright noting Hurston’s language “always made black people nervous because it reflects rural diction and syntax – the creation of a different kind of English.”

But scholar Jennifer Staple4 found that to be a positive attribute of Hurston’s literary innovation. Staple wrote that the language and expressions of Mule Bone presented a whole new kind of writing that married ethnography and drama. Mule Bone demonstrated how Hurston “embraced the anthropological method to engage in the candid inscription of Eatonville’s folklore…[Hurston] resisted the dramatic practices of her predecessors by employing novel artistic techniques that reinvented the fields of theater and anthropology.”

Staple noted how oral tradition – the way African Americans actually speak of their experiences – “was one of the most important aspects of Hurston’s realistic representation of Eatonville:” “Mule Bone employed oral tradition to exemplify the ethnographic concepts of ritual, performance and social structure,” she wrote.

Gates went on to call the Mule Bone “a false start that remains one of American theater’s more tantalizing might-have-beens.” Gates also lamented the unfulfilled promise of a play: “Had they not fallen out, one can only wonder at the effect that a successful Broadway production of Mule Bone in the early 1930s might have had on the development of theater.”

It’s a provocative point to ponder. But it also inspires us to question of how Hurston’s legacy of marrying ethnography and literature might have been altered had she been willing to compromise with Hughes on the theme of the play rather than adhere to the intention of representing the people of Eatonville. If Mule Bone had been successfully produced in the 1930s as a tale of a love triangle rather than a version of an African American folktale, would she have been encouraged to abandon the anthropological aspect that is critical to her literary legacy?

This is especially interesting to consider upon the publication of Barracoon which for so long went sat unknown because of the very traits it has in common with Mule Bone – its commitment to authentically representing African American vernacular, folk traditions, socials customs and experiences. Publishers in the ‘30s believed that these characteristics wouldn’t appeal to mainstream readers.

However, as of June 24th, Barracoon is in its 11th week as a New York Times bestseller, where made it to the #2 spot. It’s taken several decades but maybe at long last we’re able to appreciate Hurston’s steadfast (and stubborn) commitment to her literary integrity.

For further research:

Search for Zora Neale Hurston, Langston Hughes and the Harlem Renaissance for thousands of results, including biographical information and scholarly article, as well as full-text poetry, drama, prose and essays by the authors.

King, L. (2008). The Cambridge Introduction to Zora Neale Hurston.

Huggins, N. I. (2007). Harlem Renaissance.

Hurston, Z. N. (2008). Zora Neale Hurston: Collected Plays.

Patterson, T. R. (2005). Zora Neale Hurston and a History of Southern Life.

West, M. G. (2005). Zora Neale Hurston and American Literary Culture.

Carson, W. J., Jr. (1998). Zora Neale Hurston: The Early Years, 1921-1934 (Order No. 9841711).

Freeman Marshall, J. L. (2008). Constructions of Literary and Ethnographic Authority, Canons, Community and Zora Neale Hurston (Order No. 3332321).

Hill, L. M. (1993). Social Rituals and the Verbal Art of Zora Neale Hurston (Order No. 9333641).

Park, J. M. (2007). “I Love Myself When I Am Laughing”: Tracing the Origins of Black Folk Comedy in Zora Neale Hurston's Plays Before “Mule Bone” (Order No. 3269998).

Sanchez, N. T. (2015). "He Can Read My Writing but He Sho' Can't Read My Mind": Zora Neale Hurston and the Anthropological Gaze (Order No. 1592060).

Works cited:

-

- By, F. R. (1991, Feb 15). A Difficult Birth for 'Mule Bone'. New York Times (1923-Current File). Available from ProQuest Historical Newspapers

- Johnson, S. D. (2011). The Fire that Genius Brings: Creativity and the Unhealed Companionship Between Zora Neale Hurston and Langston Hughes (Order No. 3597028). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

- Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. (1991, Feb 10). Why the "Mule Bone" Debate Goes On. New York Times. Available from ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

- Staple, Jennifer. (Winter 2006). Zora Neale Hurston’s Construction of Authenticity Through Ethnographic Innovation. Western Journal of Black Studies (30:1), 62-68. Available from ProQuest One Literature